Thus, Hurvitz adds the collocation of d-r-sh and some reference to God’s commandments to the list of linguistic features that marks Psalm 119 as Second Temple literature. This usage is familiar to any student of rabbinic literature, where the object of midrash- itself a Late Biblical Hebrew word (occuring only in 2 Chronicles 13:22 and 24:27)– is the biblical text. Biblical verses in which the object of the verb refers to God’s commandments, rather than God or God’s word, occur only in Psalm 119 and in the Books of Ezra (7:10) and I Chronicles (28:8). In the rest of the Hebrew Bible, when the root refers to some aspect of the religious experience, the object of the verb often refers to God (or another god) or God’s word. Similarly, the semantics of the root d-r-sh (translated here “to turn to”) in these verses also exemplify Late Biblical Hebrew. The word piqqudekha in Psalm 119 shows this same Aramaic influence, which most likely occurred during the exile, so Hurvitz considers this word to be a linguistic marker of the psalm’s post-exilic date. The use of the root in the semantic sphere of commanding occurs in post-biblical Hebrew literature, probably under the influence of Aramaic, where p-q-d typically refers to commands. In the rest of the Hebrew Bible, the root p-q-d (source of the word piqqudekha) refers to counting or appointing, rather than to commanding. Unlike other, more common words (such as tora or mitsva), however, this word occurs only in the Book of Psalms. קיט:קנה רָחוֹק מֵרְשָׁעִים יְשׁוּעָה כִּי חֻקֶּיךָ לֹא דָרָשׁוּ 119:155 Deliverance is far from the wicked, for they have not turned to Your lawsīased on context, the word piqqudekha (“Your precepts”) in verses 45 and 94 is a synonym for commandments. The language of Psalm 119 is closer to the language of these later texts, as well. To these two strands of inner-biblical evidence, Hurvitz joins the evidence from post-biblical Hebrew, such as the language of rabbinic texts and the Dead Sea Scrolls. On the other hand, he points out differences between these same terms and those that occur in books composed in Classical Biblical Hebrew, such as the narrative prophetic books. On the one hand, Hurvitz observes similarities between Psalm 119’s terminology and that found in biblical books unquestionably from the Second Temple Period, such as Ezra and Chronicles (דברי הימים). Avi HurvitzĪvi Hurvitz of the Hebrew University has made the case for Psalm 119’s late date in his book entitled בין לשון ללשון (literally, “between language and language”), which establishes firm criteria for identifying Late Biblical Hebrew (the post-exilic phase of Hebrew within the biblical corpus) and distinguishing it from the classical language. Psalm 137 (“By the Rivers of Babylon”) which some traditional commentators recognized as late (or, in their terms, not composed by King David) because of its mention of the Babylonian exile, is more the exception than the rule. Language, that is the very wording of the Psalms, is the only effective means of establishing any Psalm’s date, because the Psalms, in general, only rarely refer to easily identifiable historic events.

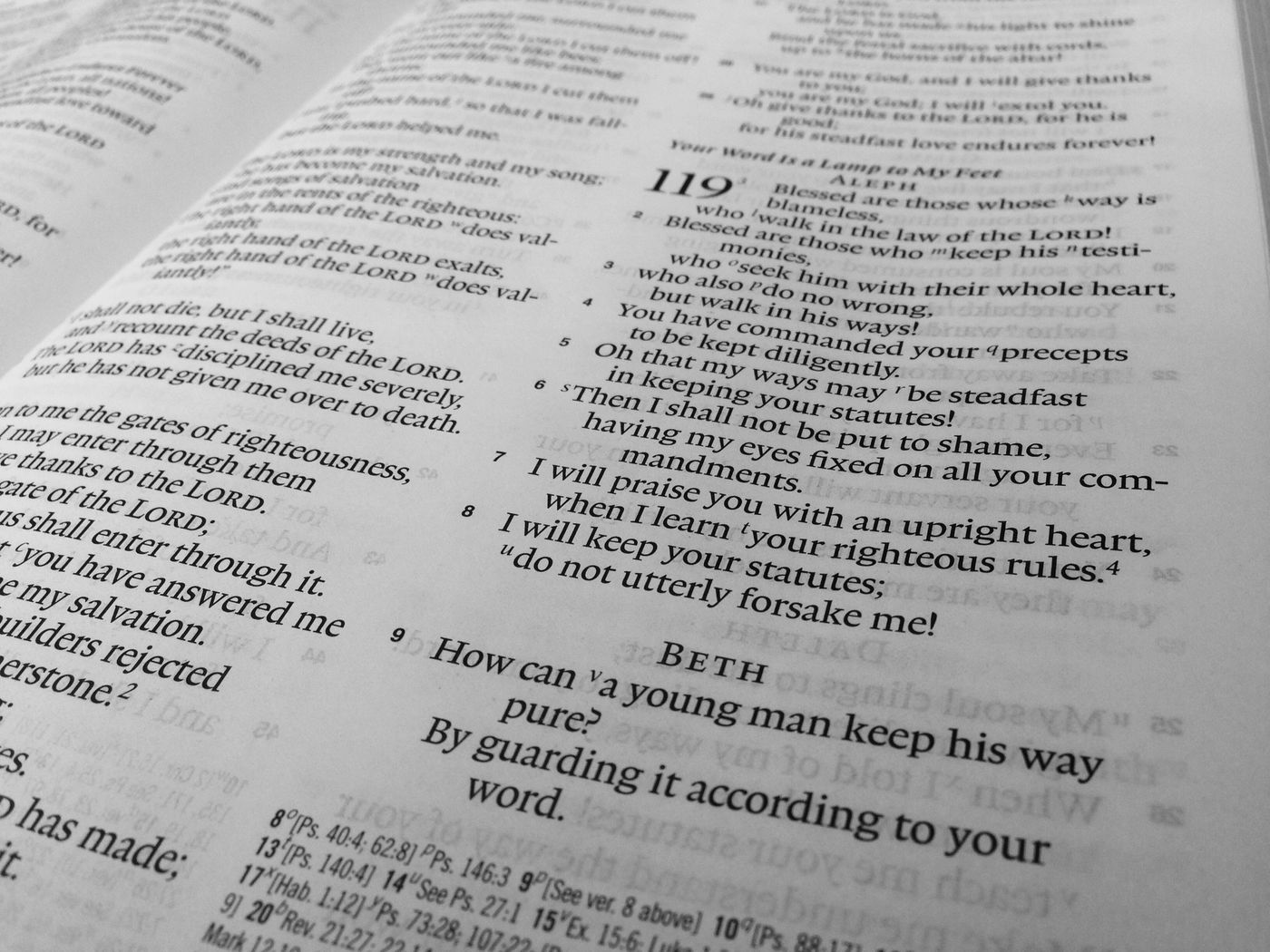

The best evidence for this conclusion is linguistic: Psalm 119 uses Late Biblical Hebrew as opposed to the Classical form of the language. Modern scholarship dates Psalm 119 to the Second Temple Period. The Psalm thus reflects the development of the idea of Torah study in the late biblical, pre-rabbinic period. My purpose here is to consider Psalm 119’s theology in light of some of the modern scholarly evidence for the Psalm’s relatively late date. While not quite striving for the rabbinic ideal of torah lishmah (Torah study for its own sake), Psalm 119 definitely anticipates rabbinic Judaism’s commitment to Talmud Torah as a mode of divine service and a path to God. In its 176 verses, eight for each of the twenty-two Hebrew letters, the psalm implores God by expressing a profound love of God’s Torah and a deep desire for its knowledge. Psalm 119 is a “must read” for anyone devoted to Torah study as a religious value.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)